Opinion

Behind the numbers

by Adrian Beney - 10 May 2023

Adrian Beney looks beyond the headlines of the latest CASE-Ross Support of Education, United Kingdom and Ireland report.

A record year for philanthropy to universities in the UK and Ireland. The President of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) and the editorial board for this year’s annual survey of fundraising in universities are right to celebrate a year in which the level of philanthropic commitments made to higher education in our islands has not only recovered to pre-Covid levels but surpassed it. Nearly £1.5 billion which will provide financial aid for those who could otherwise not afford higher education, fund research projects and infrastructure of the kind which allowed the University of Oxford to produce the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid vaccine in record time, and a host of other benefits.

The value of giving

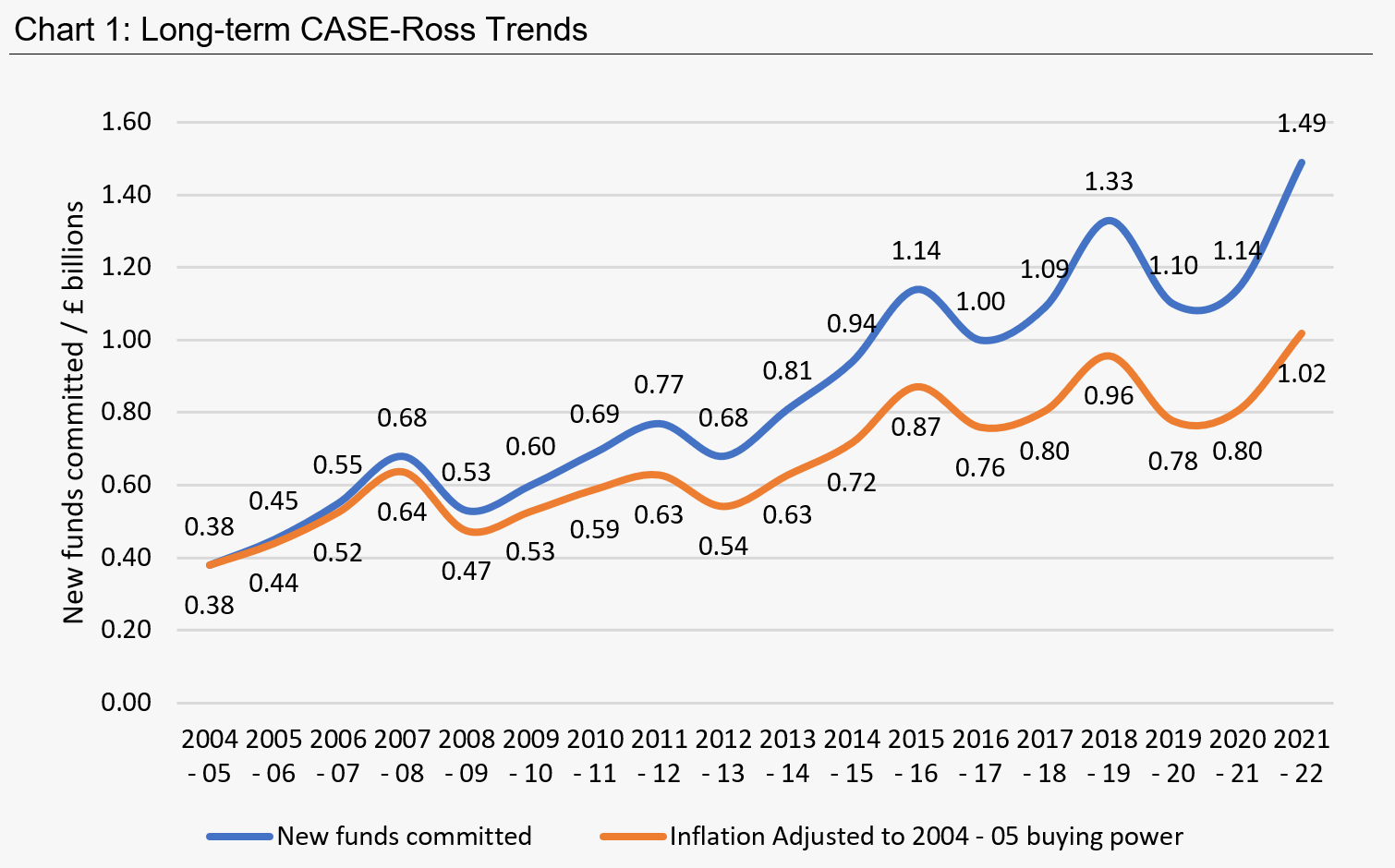

So far, so good. But what happens if we drill into things a little further? CASE has published a chart showing the amount of money committed to universities in the survey over time. (Participation is not consistent from year to year, but most of the big players are in the survey most years.) In Chart 1, we’ve reproduced that data, but we’ve also added an inflation-related buying-power adjuster. With inflation at a 30-year high, this is becoming increasingly important, and what it shows is that the three peak years since 2015 – 16 are rather more closely bunched than the raw data implies. We don’t want to be killjoys though: even taking inflation into account, 17% more money was raised in real terms last year than six years ago, and 6% more than in the last full pre-Covid year.

Looking further back, there has been around a 60% growth in real-terms funds raised since we wrote the Review of Philanthropy in UK Higher Education (Pearce Report) in 2012, and a growth of 93% in absolute terms. All this with a staff contingent which has grown by around 40% since 2012.

Who's raising the money?

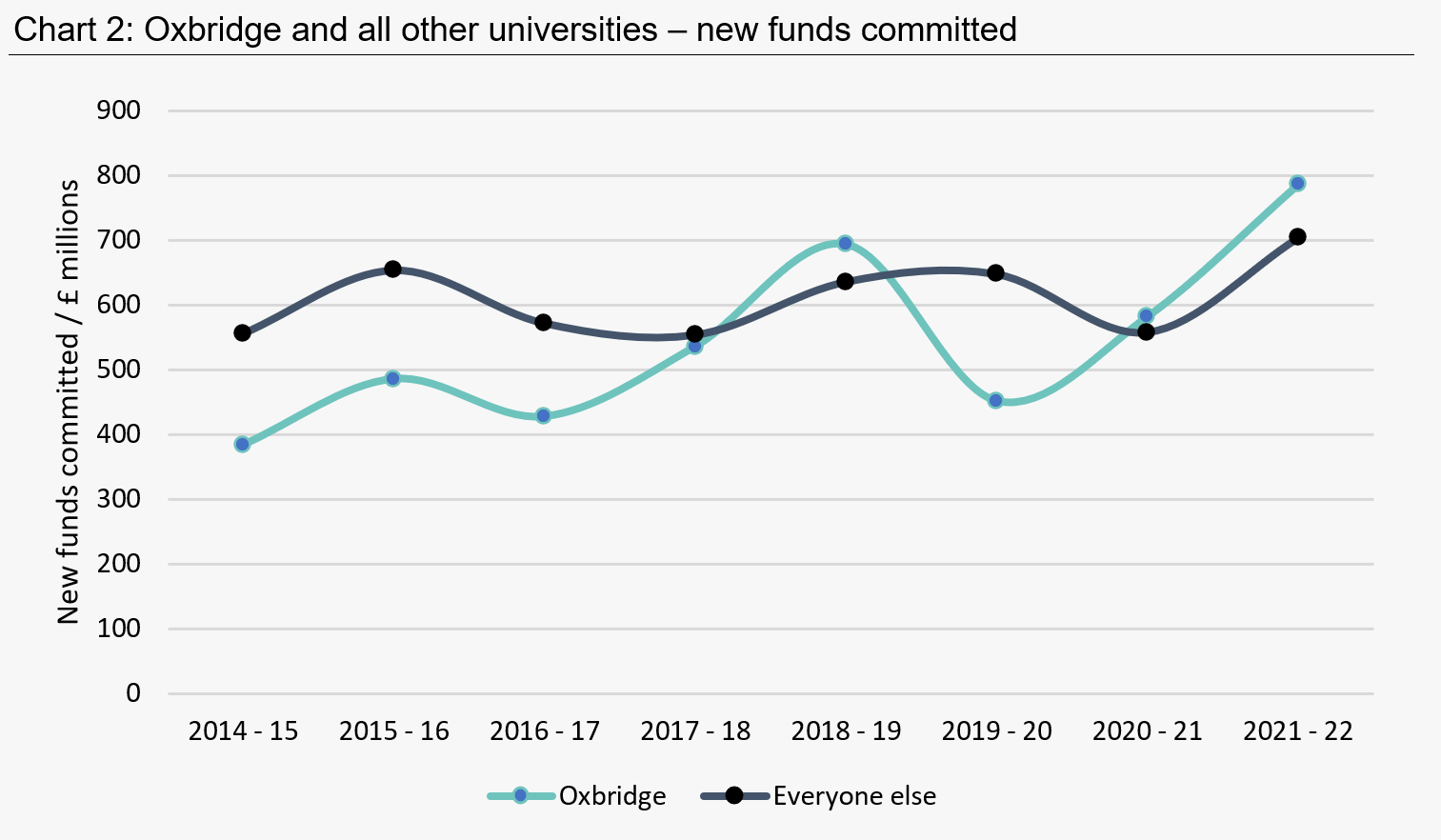

CASE is a little coy about naming explicitly the two institutions which have sat consistently in its “Elite” cluster group. But data in the public report reveals the unsurprising fact that these are the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. In three of the last eight years these fundraising powerhouses together raised more than the whole of the rest of the sector combined, and even in the years where they trailed, they never raised less than 70% of the whole of the rest of the sector.

Two important questions arise from this: are there other universities in the UK and Ireland which could raise as much as Oxford and Cambridge, and for those who can’t, what should they do instead?

When we did the research for the Pearce Report back in 2012, we found there were very strong correlations between investment in fundraising and the likelihood of raising money, and also a strong correlation between research quality and fundraising success. But because those who’d invested the most in fundraising tended to be those with very high research rankings, it was very hard to argue that research quality was, in and of itself, the cause of the increased fundraising success. There have certainly been very large gifts whose focus has been research. But then there have been large gifts for student support as well, and the need for undergraduate student aid is entirely independent of research quality.

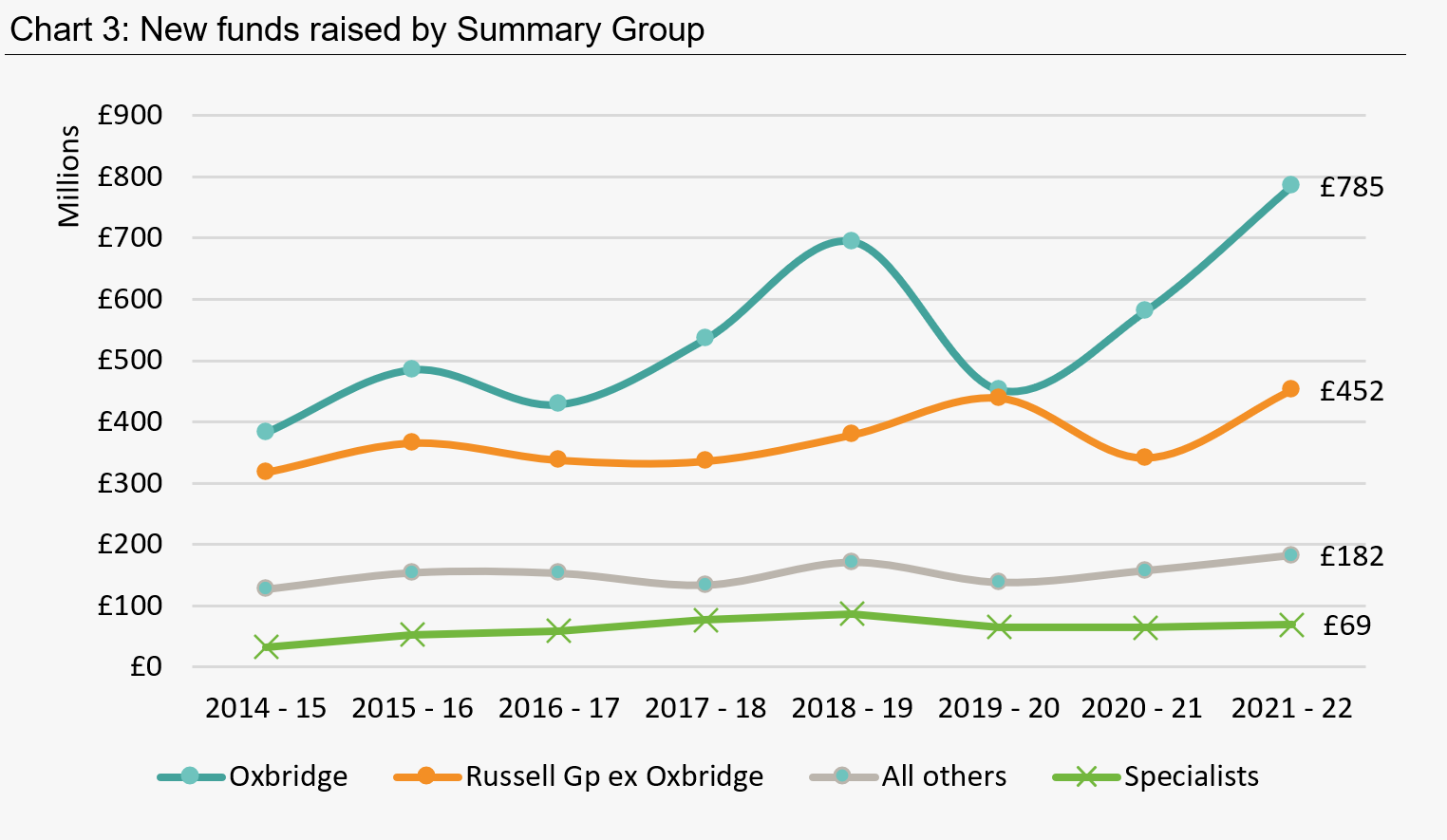

To explore this, using the public information, we have split the data into different groups. Chart 3 shows new funds committed (i.e. fundraising success) for Oxbridge, for the other Russell Group universities, and then for all other universities except the specialists like the London Business School, the Courtauld, the Institute of Cancer Research and the Royal Academy of Music. We can see that between 18 and 22 non-Oxbridge Russell Group universities have routinely been raising between two and three times as much as their non-Russell Group colleagues (compare orange with grey).

So, is membership of the Russell Group a ticket to fundraising success? The report says no. CASE has included some detailed discussion of their cluster analysis methodology this year. Seven of the 22 non-Oxbridge Russell Group universities fall into the “established” category this year, with the remaining two thirds of the group falling into the “moderate” cluster. This suggests that, even within the Russell Group, there are Development Offices whose consistency and “establishment” in the university has room for growth in profile and success. And it means that the majority of the funds raised in the Russell Group line probably came from just seven of the 22 universities.

Could those seven Russell Group universities, plus the other three “Established” institutions be raising as much as Oxford or Cambridge? Data alone can’t answer that question, but we can look at inputs and outputs. Oxford and Cambridge had, on average, 241 fundraising staff and 97 alumni staff each last year. The Established group had, on average, 35 and 18 respectively, or just one sixth as many staff. Oxford and Cambridge provide attention to their alumni at the rate of roughly one member of fundraising and alumni staff per 1,000; the same calculation for the Established group is one per 5,300. Although alumni are by no means the only constituency from whom funds are raised, and there are other institutional differences, the variance in inputs is stark.

Beyond the Russell Group

Beyond the Russell Group, in the latest year, 54 universities raised around £182 million in total, while nine specialist institutions raised £69 million.

We think that a “big question” for the sector to ask is what could those 54 universities, and others like them who do not take part in the CASE-Ross survey, do to boost the money they raise? Is it about institutional priorities, or confidence, or investment in fundraising, or availability of suitably experienced fundraising staff?

In reality, it’s probably about all of these. Vice-Chancellors have a lot on their plates. Domestic student recruitment in a “recovering from Covid” age is a turbulent thing, and international student recruitment is complicated by the geopolitics of this decade. Successful fundraising on a big scale does require the personal attention of a leadership which might be focussing on other things. But, for example, successful corporate partnerships, trust fundraising and building a base of mass giving including legacies, can be done without asking for much time from a Vice-Chancellor.

Confidence to fundraise remains something hard to grasp in some places. Some institutional leadership teams are comfortable in their own skins, in their personal relationship with money, with the idea of Higher Education as a cause and in the power-dynamics of relationships with donors. These are the leaders who set a tone for fundraising success. Others find this much harder. If universities want fundraising success, then these factors need to be considered when making appointments both to institutional and academic leadership.

The nine specialists that reported in the latest year raised £69 million – and their median new funds committed was twice that of the sector as a whole. This group contains fundraising operations which range in size from that at the London Business School and the Institute for Cancer Research, through the Royal Academy of Music, to Scotland’s Rural College and the Royal Agricultural University. What they have in common, despite disparate size and disciplines, is their focus on a relatively narrow range of academic disciplines. This gives them focus for their cases for support, and while it may limit their prospect pools, it also can make their identification a little easier. Most of their donors care deeply about their particular specialism. Specialists that are not active in fundraising should look at what their peers are doing, and those that are already active should, despite the difficulty of finding additional investment, capitalise on their ability to tell a focussed story with passion, experience and expertise.

Investment in fundraising needs to be made for the long term and at an appropriate level. This is not an argument for huge Development Offices in small institutions. But it is to argue that staff appointments need to be made at the right level in institutional structures, and resourced appropriately.

And finally, where will we find fundraising staff? Since we wrote An Emerging Profession: The Higher Education Philanthropy Workforce, we have seen increasing dialogue and movement between the HE sector and the conventional charity sector. This is good news; widening the skills base of both. But it is not enough. CASE’s graduate training programme has resulted in some notable successes to be celebrated. We should be exploring more intentional relationships with the students who’ve been successful telephone fundraisers and working with careers services to build aspiration. But we also need good senior management in fundraising offices, with intelligent KPIs which encourage good fundraising behaviour and collaboration across teams. Few gifts are the result of one person’s work alone, and we need to create an environment in which team success is celebrated as much as reaching individual fundraising targets. This will improve job satisfaction and staff retention.

From whom has the money been coming?

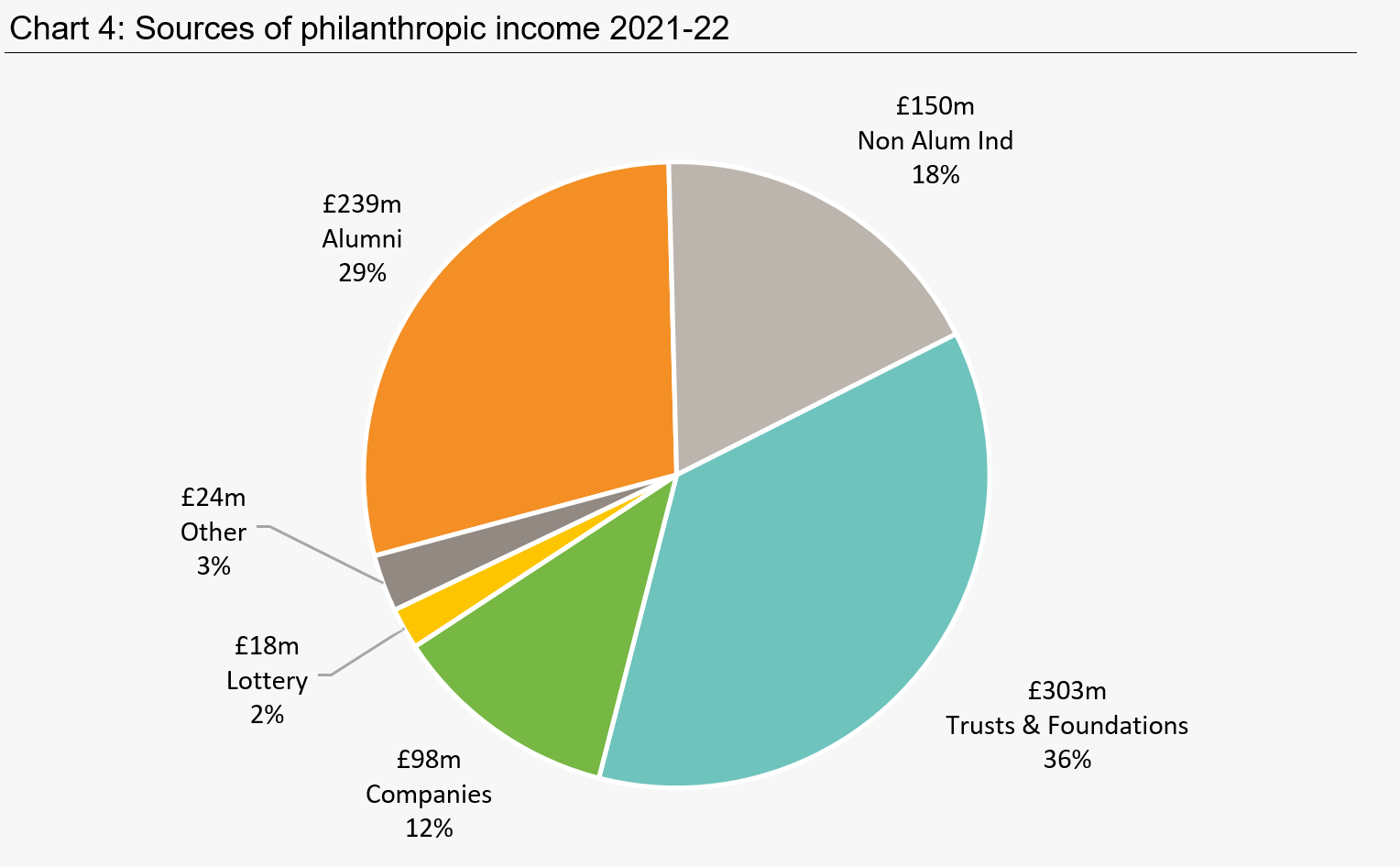

This varies a lot across the sector. Trusts and Foundations account for the largest single group, although this will be split between those whose grant making has developed a long way beyond its founder, and others which remain an expression of the philanthropy of one founder or family and are essentially vehicles for individual giving.

Corporate giving remains dismally low in the Higher Education sector. Within the 85 institutions which reported the split between donor constituencies, a total of a little under £100m was given in corporate donations. Although the CASE-Ross reporting rules exclude corporate “sponsorship” as opposed to “giving” and so overall support by the commercial sector to universities may be understated, we remain puzzled by the level of inattention to this sector. Few offices have dedicated corporate philanthropy fundraiser(s), and few universities have taken a strategic, holistic, relationship management approach to its most important corporate partners. This may be because it is hard to do this without cooperation across an institution, to pull together research office staff, academics, careers service people and so on. But the small number of examples of eight-figure gifts that have happened in recent years show the potential.

And then to legacy income. The report shows that 10% of all funds received came from legacies, and since 47% of all cash comes from people, this means 21% of all the funds received from individuals were in the form of legacies. This is consistent with research we’ve carried out as part of our Regular Giving Insight and Benchmarking programme. This is a really important and almost universally underexploited income stream, especially in the light of the impending cascade of wealth to the next generation from asset-rich Baby Boomers. Yet, legacy fundraisers report real difficulty obtaining budget for legacy marketing, and in many universities, there is very little linkage between mass fundraising and legacies. But our research shows an intimate link between mass giving in-lifetime and the likelihood of someone leaving a legacy. And the CASE-Ross report shows that in the top four performing clusters (>= Developing), legacy income accounts for an amount equivalent to between one fifth and one third of the income from face-to-face fundraising. We think it would be interesting to compare the resource input into these two areas in the same way.

We are sceptical about the numbers reported for income from what CASE calls “mass solicitation” triggers – that is, direct marketing income. CASE reports a total of around £11.4m from those triggers within the 55 Established, Moderate and Developing universities. Yet our own Regular Giving Insight and Benchmarking project, covering the same period, reported £7.7 million from just 12 of those universities. Given what we know about the difficulty of appeal attribution and recording, having seen first-hand millions of lines of raw data, we think this is under-reporting the success of mass marketing activity.

Participation in the survey

An appendix to the report shows that participation in the survey has dropped from a peak in 2013-14 (78% of UK HEIs) to just 52% in the most recent year. It’s welcome that all the Russell Group universities are back in this year, but really concerning that just 2 out of 9 Welsh HEIs took part (Swansea and Cardiff.) On the bright side, as a firm based in Scotland, we want to celebrate that 68% of Scottish and Northern Irish HEIs took part.

It’s almost exclusively the small fundraising offices that don’t take part, and we think that CASE needs to think about the complexity of aspects of the survey if it is to increase participation again.

Digging even deeper

As ever, if anyone would like our help in understanding their own numbers in detail and identifying where they can make the most effective interventions in fundraising strategy, please get in touch.